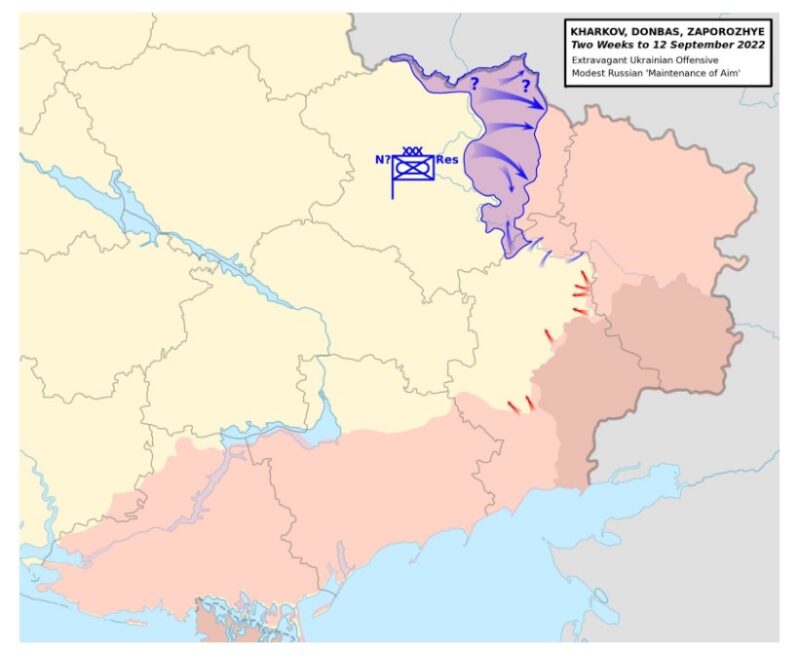

The Russian military sustained a severe loss in September in the Kharkov region, allowing Ukrainians to capture vast swaths of strategic territory in a lightning offensive resulting in at light loses. Territory that Russia had previously heavily bled for in protracted battles to win. In a rushed ad-hoc general retreat Russia even left behind considerable quantities of usable equipment.

It will become clear the defeat – which was real – was much less the result of any incompetence on the part of the Russian soldier or even general, and much more the result of the objectively impossible situation the Russian political leadership had placed the military in, expecting it to fight the largest land war in Europe since WW2 without providing it with the manpower for the job.

On September 6 the Ukrainians struck the Russian line of control around Balakleya in the Kharkov region headed east. Russian “lines” here consisted of outposts and tripwire forces. A mix of Russian Rosgvardia police, Lugansk mobiki, and some Russian regulars, particularly artillery and armor as a small “mobile reserve”.

Against this colorful mix, the Ukrainians had amassed half a dozen full brigades, several of them mechanized. The Ukrainians had amassed easily five times the forces the Russians had here. Moreover, the Ukrainians were perfectly contended to bypass the defenders. To pour into any gaps, and head into Russian depth while leaving the bypassed defenders to be dealt with by follow-on echelons.

The Ukrainian advance was swift. By nightfall of September 7, their vanguard was halfway to the Russian logistical hub of Kupyansk. On the next day, their scouts dipped their toes in the Oskil river just south of the city.

AFU 🇺🇦 counter-offensive in Kharkiv region for the last three days 🔥 pic.twitter.com/8Mpj3fVPqB

— Tarmo 🇨🇿 🇺🇦 🇫🇮 🇪🇺 (@TarmoFella) September 9, 2022

The Russians side initially advertised that they would quickly pour in reinforcements and repel the attack. Russian state TV carried footage of supposedly massive reinforcements arriving by land and and by air.

But quickly the exact opposite decision was made. A general Russian withdrawal was ordered and on the 9th the Ukrainians entered Kupyansk unopposed. In three days the Ukrainians had covered 60 kilometers. A pace of advance that Russia had last demonstrated in March.

https://twitter.com/200_zoka/status/1568513828379586561

Not just Kupyansk. To the south the Russians were also already withdrawing well ahead of the Ukrainians from Izyum, which now lay dangerously exposed. And from the border buffer near Kharkov to the north. Along 300 kilometers of the front, the Russians were falling back behind either the Oskil or the Russian border. A retreat between 20 and 60 km, depending on the sector.

The reason the Russians opted to withdraw rather than to fight, as they first claimed they would, is that in reality they had very few reserves and these were far away. Once the Ukrainians had been allowed to mass against weak and second-tier Russian forces the game had already been lost.

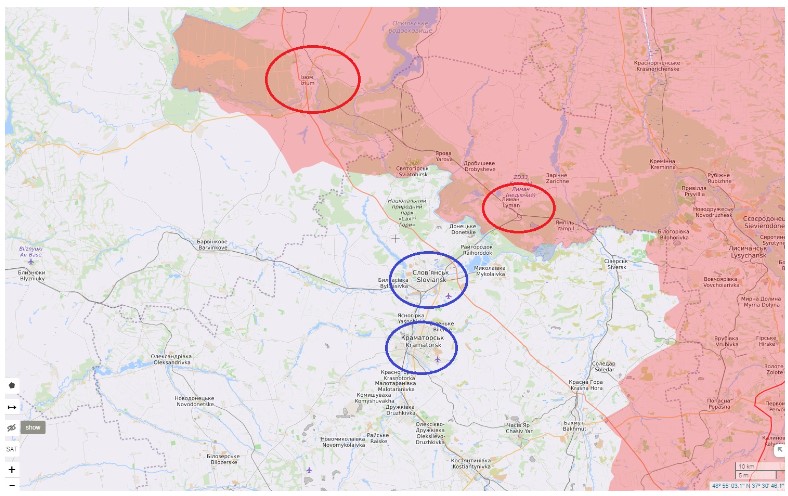

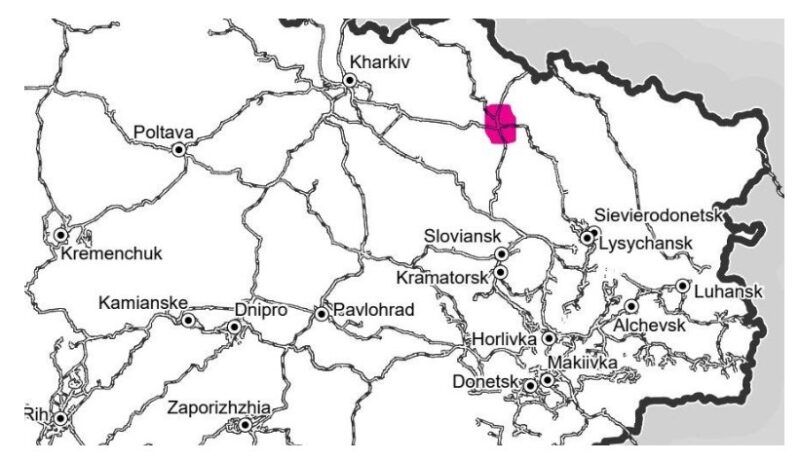

But lost now were also Izyum and Kupyansk. Izyum was the key city where the Russian army had crossed the Severskiy Donets river and had established a springboard for an advance on Slavyansk and Kramatorsk. Kupyansk meanwhile was the key railway hub to keep Izyum and northern Lugansk supplied.

To capture Izyum and expand its bridgehead had taken the Russians months of bloody battles. Now it was lost in the blink of an eye. And with it the springboard for a march on the last two remaining cities in the Donetsk region in Ukrainian hands from the easier and superior northern direction.

In a matter of days between September 6th and 12th, the Ukrainians captured nearly 10,000 square kilometers. Not counting Russia’s own advances of February-March the last time this kind of blitzkrieg happened in Europe was in 1995 in Croatia’s Operation Storm. But where the Croatian army achieved this feat against a rebel Serb statelet, the Ukrainians did it against what had been considered the world’s second or third military.

For the amount of territory that traded hands the personnel losses on both sides had been light. In the hundreds of dead rather than thousands. The Russian decision to withdraw, rather than to defend, meant that there was little fighting after the first three days. But the equipment losses on the Russian side were significant. So bad that Russia’s top military portal thundered against “Russian Lend-Lease” and called on the “supreme commander” to intervene.

What made the equipment losses worse is that by and large the gear had been captured rather than destroyed in battle. This was no orderly, centrally-orchestrated, phased withdrawal. What appears to have happened is that when the Russian command realized by how much the Ukrainians outnumbered them, and with what ease they were driving into the Russian depth, an order went out to each individual unit beyond the Oskil to turn on its heels and get behind the river as soon as possible on its own.

Anything else would have risked Russian forces becoming cut off and encircled. But with each unit now hastily withdrawing by itself a lot of heavy equipment that would have gotten in the way was left behind. Particularly any vehicles in a poor state of repair, many of them in repair yards.

So in the final tally of the Kupyansk-Izyum Offensive the Russians lost nearly 10 000 sq km, including strategic areas they had bled for heavily. They had also failed to make the enemy pay a high price for the gains and to successfully trade space for time and enemy attrition. On top of that, they — conservatively speaking — lost 100 armored vehicles that will sooner or later be turned against them. On the other hand, they did succeed in preserving the great majority of their personnel.

NATO-backed Ukrainians meanwhile captured strategic ground that averts danger to Slavyansk and Kramatorsk. But more than that, in their first large-scale offensive they showed that they are perfectly capable of carrying out competent combined-arms offensives of their own when the circumstances allow them. (There had been a previous Ukrainian offensive against the Kharkov buffer in May which was also successful but that was on a much smaller scale.)

https://twitter.com/Syricide/status/1568541737903087619

A particular feat was the way in which the Ukrainians were able to concentrate and layer their Soviet-era air defenses in a way that prevented the Russian air force from exerting its influence on the battle. You might have thought that Russian air assets could make moving large mechanized forces in the open during the day impossible for Ukraine but nothing like that transpired.

What was the cause of such a Russian defeat? For one the Russian command was working under the condition of extreme manpower scarcity compared to the Ukrainians. The Russian side was still persecuting the war only with as many men as they had brought in originally, whereas the Ukrainians had kept calling up more and more men and expanding their forces since the start of war 7 months ago.

— Marko Marjanović (@marmar_ae) November 22, 2022

In peacetime, Russia has over 900 000 men in the armed forces. But a lot of that falls on services like navy, air force, and strategic missile forces. The various land combat arms (ground army, airborne, naval infantry, and special forces) together have under 400 000 men in uniform. At the start of the war however, Putin forbade the military from deploying conscripts performing their mandatory 1-year national service. This left a pool of just 250 000 officers and kontraktniki to shoulder the brunt of Russia’s war effort on the land.

On the other side, the estimates for the size of Ukrainian armed forces by September reach as high as 700 000. (I would probably put them lower at some 500 000.) Naturally, a force of 250 000 couldn’t sustain a deployment to the battlefield anywhere near the size of what could be sustained by a total force of 500 000 or 700 000.

Aside from this general manpower superiority, the further secret to Ukrainians’ success lay in the fact that they amassed precisely against a sector of the front that the Russians had dangerously weakened.

Some of the tanks advertised as captured in Izyum by the Ukrainians. Source: Военное обозрение/Voennoe Obozrenie/Military Review

Izyum had once been home to a large concentration of Russian troops attempting to force their way to Slavyansk. But as growing Ukrainian numbers forced the Russians to abandon that ambition and to transition to defense numerous Russian regular units were transferred to frontlines in the south, particularly to Kherson. Their Kharkov right flank became a sideshow for the Russians which they hoped to hold with the most minimal numbers possible. Ukrainians had other ideas and amassed a credible assault force against it even as they amassed another such force against Kherson.

Thus while overall the Ukrainian advantage of men in the theater was under 2:1 on this neglected Russian flank it might have been greater than 3:1, with overmatch on the point of the Kupyansk spearhead even 8:1. So it would be incorrect to say that it was just a matter of overall numbers — skillfull Ukrainian positioning also played a role.

The strangest thing about this is that this Ukrainian positioning wasn’t entirely secret. For weeks leading up to offensive Russian Telegram channels were noticing heightened Ukrainian activity that suggested a build-up opposite of Kupyansk yet the Russian positions continued to be weakened. So the intelligence was there, it is just that the Russian command didn’t react to it.

This caused a great deal of anger in the Russian military blogosphere when the battle concluded so unfavorably for the Russian side, but I feel that the Russian command may not have had a choice. As said, the Ukrainians were also amassing against Kherson. Indeed the Ukrainian attempt against Kherson started more than a week before the Kupyansk operation kicked off.

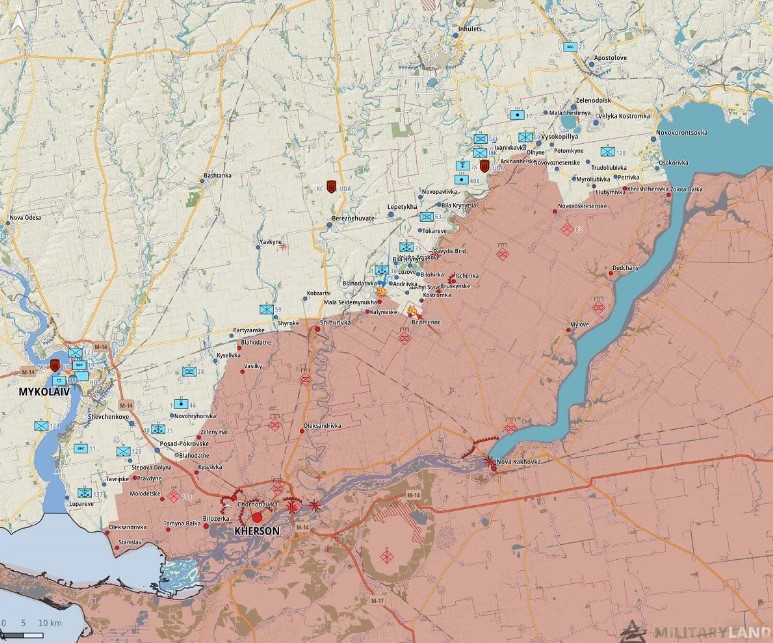

The Russian command may have felt it simply didn’t have the forces to properly reinforce both its right flank in the Kharkov region and its left flank across the Dnieper around Kherson. I think that faced with an impossible choice it opted to prioritize Kherson and hope that the Kharkov buildup was a feint, or overblown, or that its rag-tag forces there could hold. But why would it prioritize Kherson in this manner?

I think they would do that because their right-flank at least had depth. Its Kherson flank was in a much more precarious position owing to its different geography. If the worst came to worst in Kupyansk at least the forces there could be safely pulled back. But if the enemy ever managed just a 30-kilometer march in Kherson the Russian retreat would be cut off against the Dniester. While just a 10-km advance would put Ukrainian guns in range of Russian-held bridges.

There was no buffer in Kherson, no margin for error. The stakes in Kherson were simply higher. If Kherson was not strengthened to where the Ukrainians could not even get a good start, eventually losing tens of thousands to an enemy encirclement was a possible outcome. The worst-case scenario for Kherson was worse and more realistic than the worst-case scenario for Kupyansk.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can say that the Russian command didn’t do an optimal job of shifting around forces. But we must understand that they were working under the incredible strain of not having enough troops to begin with, and then having the Kherson problem hanging over their heads to boot.

Ironically the debacle in the Kupyansk-Izyum offensive ended up working in the Russian military’s favor. On September 12th the Ukrainians reached the border opposite of the Russian city of Belgorod. On September 21st Vladimir Putin declared the partial mobilization of 300 000 citizens into the ranks.

For 7 months after starting the war Putin watched as the Ukrainians generated more and more forces through successive waves of mobilization while doing nothing himself. He did not even move to make the 250 000 conscripts already in the military (150 000 in the land combat arms) deployable.

But as Kharkov-Izyum demonstrated just how unfavorable the correlation of forces had grown for the Russian side, Putin was finally forced to end his indecision.

But as it turned out, Russia was not yet done paying the price of Putin having waited so long. It would take time for the 300 000 mobiki to be trained and make their presence felt in the theater. Before that would happen Russia would suffer two more losses in Liman and Kherson.

Izyum had once been home to a large concentration of Russian troops attempting to force their way to Slavyansk. But as growing Ukrainian numbers forced the Russians to abandon that ambition and to transition to defense numerous Russian regular units were transferred to frontlines in the south, particularly to Kherson. Their Kharkov right flank became a sideshow for the Russians which they hoped to hold with the most minimal numbers possible. Ukrainians had other ideas and amassed a credible assault force against it even as they amassed another such force against Kherson.

Thus while overall the Ukrainian advantage of men in the theater was under 2:1 on this neglected Russian flank it might have been greater than 3:1, with overmatch on the point of the Kupyansk spearhead even 8:1. So it would be incorrect to say that it was just a matter of overall numbers — skillful Ukrainian positioning also played a role.

Izyum and Liman (red) were vantage points on to Slavyansk and Kramatorsk (blue) but are now lost. Source: Livemap.ua

The strangest thing about this is that this Ukrainian positioning wasn’t entirely secret. For weeks leading up to offensive Russian Telegram channels were noticing heightened Ukrainian activity that suggested a build-up opposite of Kupyansk yet the Russian positions continued to be weakened. So the intelligence was there, it is just that the Russian command didn’t react to it.

This caused a great deal of anger in the Russian military blogosphere when the battle concluded so unfavorably for the Russian side, but I feel that the Russian command may not have had a choice. As said, the Ukrainians were also amassing against Kherson. Indeed the Ukrainian attempt against Kherson started more than a week before the Kupyansk operation kicked off.

The Russian command may have felt it simply didn’t have the forces to properly reinforce both its right flank in the Kharkov region and its left flank across the Dnieper around Kherson. I think that faced with an impossible choice it opted to prioritize Kherson and hope that the Kharkov buildup was a feint, or overblown, or that its rag-tag forces there could hold. But why would it prioritize Kherson in this manner?

I think they would do that because their right-flank at least had depth. Its Kherson flank was in a much more precarious position owing to its different geography. If the worst came to worst in Kupyansk at least the forces there could be safely pulled back. But if the enemy ever managed just a 30-kilometer march in Kherson the Russian retreat would be cut off against the Dniester. While just a 10-km advance would put Ukrainian guns in range of Russian-held bridges.

There was no buffer in Kherson, no margin for error. The stakes in Kherson were simply higher. If Kherson was not strengthened to where the Ukrainians could not even get a good start, eventually losing tens of thousands to an enemy encirclement was a possible outcome. The worst-case scenario for Kherson was worse and more realistic than the worst-case scenario for Kupyansk.

Swedish weekly Nya Tider’s Foreign Editor Christer Ericsson highly recommends anti-empire.com for Russia-Ukraine news and analysis from the realist, questioning perspective.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can say that the Russian command didn’t do an optimal job of shifting around forces. But we must understand that they were working under the incredible strain of not having enough troops to begin with, and then having the Kherson problem hanging over their heads to boot.

Ironically the debacle in the Kupyansk-Izyum offensive ended up working in the Russian military’s favor. On September 12th the Ukrainians reached the border opposite of the Russian city of Belgorod. On September 21st Vladimir Putin declared the partial mobilization of 300 000 citizens into the ranks.

For 7 months after starting the war, Putin watched as the Ukrainians generated more and more forces through successive waves of mobilization while doing nothing himself. He did not even move to make the 250 000 conscripts already in the military (150 000 in the land combat arms) deployable.

But as Kharkov-Izyum demonstrated just how unfavorable the correlation of forces had grown for the Russian side, Putin was finally forced to end his indecision.

But as it turned out, Russia was not yet done paying the price of Putin having waited so long. It would take time for the 300 000 mobiki to be trained and make their presence felt in the theater. Before that would happen Russia would suffer two more losses in Liman and Kherson.

https://twitter.com/200_zoka/status/1568575201754882048

🤡"Russia is here forever"

On June 18, Alexander Sidyakin, a representative of Putin's "United Russia" party, announced the beginning of issuing Russian passports in #Kupyansk with the words "Russia is here forever".

On September 10, the occupiers fled the city in just 2 days. pic.twitter.com/uRWjwgp3ro

— NEXTA (@nexta_tv) September 10, 2022

Marko Marjanović is a commentator, analyst and the publisher of the news site Anti-Empire. Marjanović was an editor at Russia Insider 2014-2019. He has been writing on geopolitics and Eastern Europe since 2009.

No comments.

By submitting a comment you grant Free West Media a perpetual license to reproduce your words and name/web site in attribution. Inappropriate and irrelevant comments will be removed at an admin’s discretion. Your email is used for verification purposes only, it will never be shared.