All those young women with their bare feet and paper globe lamps from Habitat, talking about the Struggle. Boycott Barclays, boycott Shell, for doing business in South Africa. Boycott South African marmalade. At university, the student’s union bar was called the Mandela bar, named after Nelson Mandela, the black liberation struggle hero who had been in jail for 25 long years.

In 1990 the Apartheid regime threw in the towel; Nelson Mandela was released. Who can forget the touching footage of the dignified and noble old man walking hand-in-hand with his wife Winnie down a cheering street? Four years later he was president of a new South Africa, “the rainbow nation”, where all races were equal. South Africa got a new flag, and for many years enjoyed enormous goodwill from the world community.

But the world’s goodwill was not paralleled by continuing media interest. Journalists’ interest dropped precipitously. It was if the journalists and activists had decided that the fairy tale ended at this point. “And so, they lived happily ever after.” But the story did not end. Mandela served just one term, but his party, the ANC (African National Congress) has provided every president and government since and faces very little competition in parliament. What does South Africa look like after thirty years of non-stop ANC rule?

I decided to go down and find out for myself with the question: What is the state of the rainbow nation thirty years after Apartheid? How did the fairy story work out?

Power problems

South Africa has been experiencing rolling, planned blackouts, locally called “load shedding”, since 2008. It is a beautiful, eerie experience to drive around a big, modern city like Johannesburg during load shedding. It is true that the high-end shopping centres, the top hotels, the better restaurants, and upscale homes as well as hospitals, airports (and the presidential palace) use diesel generators or inverters and batteries to keep the power on, but the vast townships are all swathed in darkness, and the street and traffic lights are all off. Load shedding has got worse in recent years: much of September 2022 experienced stage 6 (out of 8): three periods of two or three power cuts, barely noticeable if you are upper-middle-class white (or, increasingly, black) living in a gated community (to protect against one of the world’s highest murder rates, around 35/100,000). Then you will have an inverter battery kit: the inverter plugs into the grid and converts AC into DC and charges the battery pack. When the power goes off, the battery powers the household. But such kit is expensive: up to 80,000 rand (4,000 pounds sterling) in a country with 35% official unemployment and 66% youth unemployment, and where the monthly social grant is 350 rand a month, which is the equivalent of 4 pounds a week. The poor suffer therefore from the blackouts. Cape Town city council advises city residents to take out money from ATMs beforehand (since the ATMs don’t function during load shedding), prepare food, keep fuel in the car (since the petrol stations are down), and keep cell phones and laptops charged. But in the townships, laptops are rare.

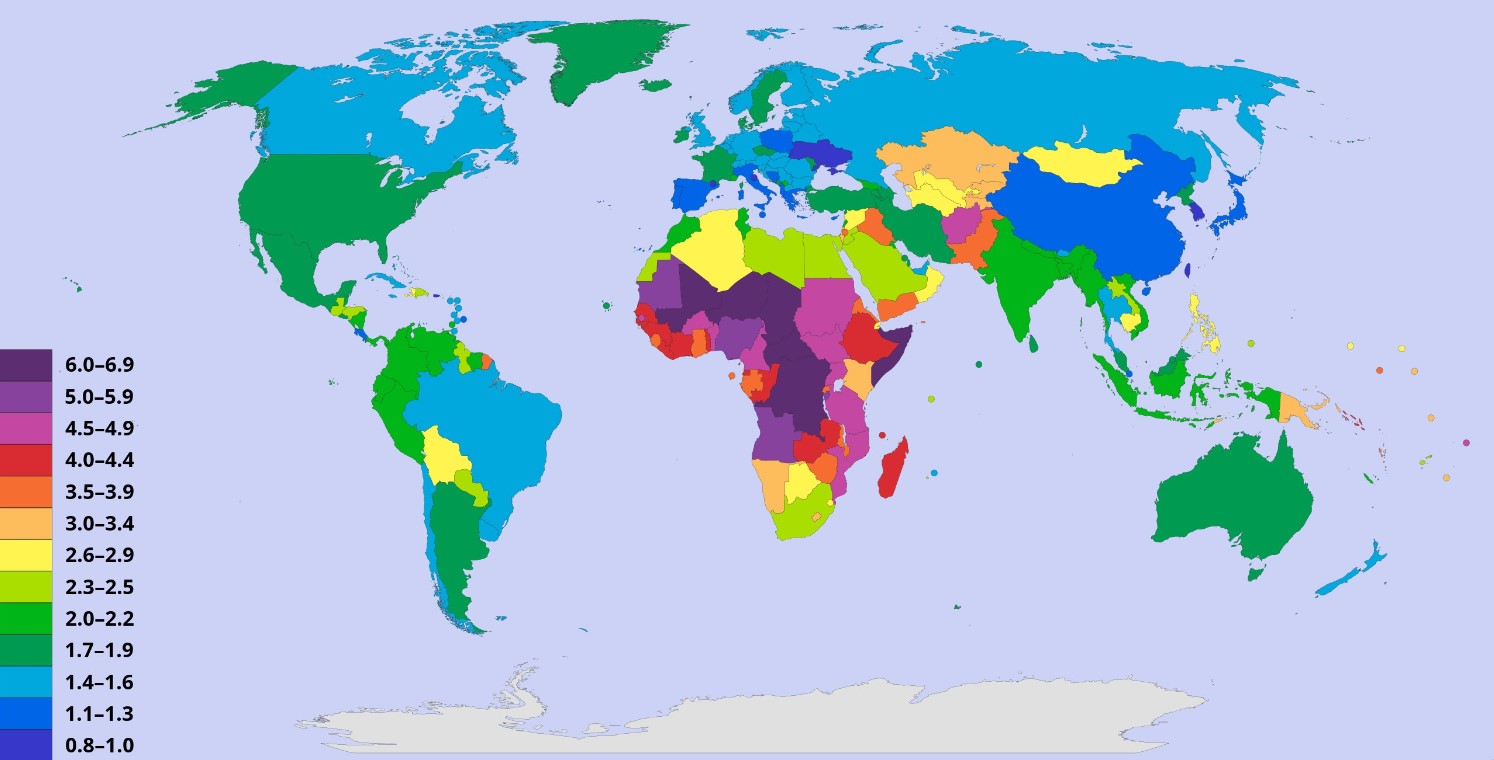

The main reason is the failure to build new power stations to accommodate an exploding population. South Africa’s population is 60 million, up from 42 million in 1994. But while the Apartheid regime built 14 power stations with 35,804 MW of capacity in the 30 years between 1961 and 1994, the ANC government, since the end of Apartheid, has built only two power stations, Kusile and Medupi, for a potential 9,564 MW. That full capacity is not in use yet.

At Kusile, in Mpumalanga province, which started construction in 2008, only four of the six units are working. Medupi was completed in 2021 but a week after opening there was a massive explosion that damaged Unit 4. Repairs are expected to take until 2024 and cost 2.5bn rand. During construction, there were several redesigns of the ongoing project. The coal mills for each of the 12 units of the two power stations had to be subjected to 11 modifications. There was redirection of the flue gas inlets, and erosion protection to the air ducts was added. Phil, an engineer who doesn’t want to give his last name, worked as a civil engineer at Medupi for eight years. Six days a week, often arriving at 5.30 am and leaving at 8.00 pm with the rest of his management team. The frustration and anger in his voice as he recalls this dismal period of his life is palpable.

“My belief is that the entire procurement system was fundamentally incorrect, and then even within what was chosen it was poorly implemented. At the start I think, if I remember correctly, there were 38 main contractor packages, but they were procured and negotiated in what seemed to be absolute silos. We would have a whole lot of completion milestones and a whole lot of access milestones, with a date to meet and a scope to meet, but when we completed them and handed them over, they were incompatible with the follow-on contractors’ date.

“You ended up in no man’s land, where we had finished but the following contractor couldn’t start. I wouldn’t say all, but a substantial number, of the 800-odd milestones that we had to meet were like that.”

“All engineering queries had a very convoluted way of getting answered or getting a response. Obviously if the main contractor on the boiler or the turbine side was having an issue they would just slow down and say they didn’t get access.

“Our requests for information, or RFIs, had an average response time of over 92 days. The industry norm is between say three and five days. Let us say we’d put a base in and there’s a query around the bolts or something, and now we wait three months for the information. By the time we get back to it, it’s all rusted and knocked over. The disruption to our production and our labour teams, and obviously the costs to us, were huge.”

Why was the construction of these power stations handled so badly? I visit Chris Yelland, a consultant electrical engineer in his house in posh North Johannesburg.

Yelland is South Africa’s best known media commentator and analyst on engineering affairs and, sitting in his fragrant English-style garden, chooses his words carefully to explain the problems at Eskom, the state electricity company.

“When I was at university there was one black student in my year. If you go to the University of KwaZulu-Natal today, you probably find there is one white engineer in the class. When I came out of university as an engineer I was as good as useless. University education doesn’t create an engineer. It just gives you some starting tools, and what is really required then is a good training. I did my training in the UK as a graduate apprentice, after which I could become what is known as a chartered engineer.

“On top of that, you need years of experience, and everyone needs very good mentors: it’s not a process that happens overnight, and it’s still a process that has been playing out since 1994. Before 1994 there were no black engineers.

“Now the universities are full of black students becoming engineers and they still have got maybe 10-15 years to go before you can say they are experienced engineers, and they will reach their peak of their career maybe when they’re 50 years old. So, at senior levels today, what does the racial balance look like? It is changing fast.

“The process of change has been accelerated through the black empowerment processes; some would argue accelerated to the detriment of the organisation. I will give you an example.

“Eskom had very aggressive targets for changing the gender and racial profile of their entire staff, not just engineers, and people’s bonuses depended on achieving these targets in the HR departments. This transition happened quite quickly at Eskom. Maybe some would argue that it’s the root of some of their problems that they face today over the skills issues.

“All the white engineers were given opportunity for voluntary retrenchments and pay-outs to encourage them to make space for young, upcoming people. They left voluntarily with a bit of incentive and sometimes also a feeling that they had reached the ceiling. If they wanted to grow further, they had to go outside Eskom.

“For example, a guy I knew I thought would become the CEO of Eskom joined Shell International and became top executive. He left because his growth prospects at Eskom were limited because of the aggressive targets for black empowerment.”

The construction delays and issues have been one thing, operating problems another. You often get these cascade effects. Strikes at the coal stock yard at Medupi mean that the management bypass the place by running the conveyor belt that links the coal mine directly to the boiler area to the max, breaking the conveyor belt. Trucks are then hired to convey the coal from the mine to the plant. But when the conveyor belt is fixed and the strikes stop, the truckers don’t want to give up serving the plants. They have an earnings stream they won’t give up. So, they are kept on. Then, according to local media, a coal “mafia” replaces the high-grade coal from the Medupi mine and sell it abroad at a good price in these energy-hungry times. The “wrong coal”, of lower grade and with pebbles and rubble, is trucked in from another mine, instead, potentially damaging the boilers. More recently the Johannesburg Sunday Times, South Africa’s largest paper, reports on the latest scam: bribed staff insiders at Eskom who deliberately break plant equipment so that they can get paid overtime to fix it, buying spare parts at a premium price from companies with whom they are in secret collusion.

The load shedding story is Kafkaesque and never-ending: when the power is off centrally, cable thieves go into substations to steal cables. When I visited the town of Benoni, east of Johannesburg, I saw a white man almost in tears in front of a small electrical cabinet that supplied power to the street, including his furniture store.

In the last power cut, thieves had stolen the wiring that supplied power to the street. So when the power came on, there was still no supply to his store. If the problem was not fixed, he would have to put his staff, nearly all black, on “short pay”, with knock on effects on the rest of the local economy. Just a small illustration of how power cuts affect everything.

There is a video on YouTube of a cable thief who was severely burnt as he mistimed the theft: the central power came on just he was yanking off the last cable. Staggering out of the substation, as captured on CCTV, at least he survived. I was shown a repaired substation that had burned down and caused a local power cut after a squatter placed himself and a mattress on top of one of the transformers in the cold winter veldt night, resulting in the blanket catching fire. This led to the squatter falling into the three-phase step joints, causing a fatal electrocution. The substation had been repaired by the local community: the Emfuleni Rate Payers’ Association. This community group consists of local professionals, project managers and engineers, mostly white, who, fed up with the ANC-run municipality’s inaction over things like this, hire their own diggers and do their own repairs, paid for by volunteer funding.

Sewage troubles

The two engineers at the head of the Emfuleni Ratepayers’ Association, Gerhard and Kobus van Rensburg, brothers, one a software developer, the other a former power engineer, drive me from the ruined substation some kilometres to a landscape littered with garbage as far as the eye can see. A group of squatters stand at the entrance from the main road, on plastic chairs of the type you see in holiday resorts, surrounded by garbage, some of it smoking. They pocket money from the trucks that practise illegal fly tipping in the area.

Eventually the car in front stops in front of a derelict structure, about two metres square. It is a sewage pump that, when working, serves to gather up all the sewage coming through pipes in the neighbourhood to this point from where it is then pumped onwards to a waste treatment plant. Pumps are notoriously vulnerable to tampons, bricks and other debris coming through the sewage system, but this looks as if it has been broken for a long time. When the pump is not working, the sewage bubbles into the nearby Vaal River, which provides water for 13 million people in the greater Johannesburg-Pretoria area.

Gerhard van Rensburg tells me in an interview in the rather stripped-down building that serves at the ratepayers’ association’s headquarters (they have been burgled six times in the past two years):

“The Green Drop Report that was released by the government in March this year really shows some systems have failed dismally at the 850-odd wastewater treatments across South Africa. Only 15 have received the Green Drop certification, the rest are dysfunctional to a great degree. Our focus is not on driving profit but on driving the solution to the problem because the 50,000 litres of raw effluent that enters our water catchment systems per second is a problem of gargantuan proportions.”

He envisages a series of “bioreactors”, thousands of specific species of plants placed in containers over an area of 400 square metres. These constructed wetlands use natural microbes that exist in the plant root systems to cleanse the waste. The wate treatment wetlands can be landscaped attractively, and have low maintenance costs and a small carbon footprint. Rensburg and his brother have won an award from the Middle East to develop the project, and he has the backing of the local Chamber of Commerce to try and realise the project on a commercial scale. One option is to then hand over control of the sewage works to the local community, not necessarily the ANC municipal government, as some towns in rural South Africa have done, since the ANC is “not doing its job”,

Rail decline

Cut from the sewage area to another example of South Africa in decay: the once proud railway system, built by Victorian, usually British, engineers, and once one of the wonders of Africa. (William Brounger, the father of South African railway engineering, was a Londoner.) Farmers could send their produce from the smallest towns of the karoo to any one of the thousands of stations across South Africa. A railway museum run by John and Jacques Wepener is packed with railway paraphernalia, station signs with alluringly English names like Worcester. There are breakfast menus from SAR’s 1960s heyday. Old whistleboards, semaphore signals and locomotive number plates. Wepener senior reminisces about the days when working with the railways was a way of life for thousands of employees. He tells me it was accepted that if a white could not get a job anywhere else, he could get a job with the railways. This was during Apartheid, with its separate ticket halls and carriages for whites and blacks. Of course, the Apartheid system was wicked, but the railway system has been effectively dismantled since, to the loss of all, and black workers have been pushed into using minibuses, which are troubled by violence, and relatively expensive.

The rot began with the abolition of the dedicated railway police, reports David Williams, a financial journalist and author of a report on South Africa’s railways. Incompetent, politically appointed and corrupt management made things worse. One chief executive, an ANC crony, ordered expensive locomotives from Spain that proved to be too high for South Africa’s tunnels and had to be sold off at a loss, says WIlliams. Covid accelerated the process of dereliction as thieves stole overhead cables, railway station fittings, and rail track, which are smuggled abroad for scrap. Even sleepers, made of increasingly rare hardwoods such as teak and ironwood, are stolen. There are some railways still intact, but many are not. The diagram shows the decline of rail travel. It is stark: if you go to Johannesburg’s suburban railway stations like New Era, Parys, Benoni or even the station built for the World Cup Finals in 2010, Nasrec, it is just a tragic sight of ruined waiting rooms, drooping cables, rail tracks stripped both of sleepers and rails.

Squatter camps occupy many of the station platforms, adding to the legal headache should PRASA, the railway operator, wish to restore the stations. Between cities, some tracks are still functional, but as overhead wires have been stolen the rail operators have to switch to diesel locomotives. But dangling “droppers” – vertical support wires – now present an ever present threat, forcing trains to zig and zag from up to downlines to avoid the stray droppers from smashing locomotive windscreens, says Wepener.

I walk around the Benoni station with Jan, a former Apartheid era policeman with Ray-Ban Wayfarers and a drooping white walrus moustache which accentuated the downward turn of his mouth. Wading through the garbage in what used to be a ticket office, he keeps an eye on his parked car which has attracted the attention of station squatters, and peers out over the platform. He addresses, through me, “Western liberals”: “You were the people that were pushing for this. The country was given to the ANC in a functional state. This is what has happened after 30 years. Where are you now, what help are you giving to this country now?”

There is a proportion of whites who, like Jan, miss the tidy streets and the functioning power and train and sewage networks of the old Apartheid South Africa, where the blacks were neatly tucked away in the homelands and the dirt poor townships, needing day passes to come to the orderly white city centres. (They had to be out by nightfall or be arrested.) After the camera stops rolling, one or two say something like, “In Africa, they don’t ‘do’ maintenance.” Or, “Have you seen South Africa’s results in the TIMSS survey?” (South Africa was near the bottom in this international school maths survey.) But most of my interviewees genuinely say Apartheid was terrible and that the problems today are not civilisational or cultural, but political. The ANC, post-Mandela, botched it: corrupt, incompetent, power hungry, elevating cadres, family and friends to positions in the administration to which their skills are unsuited. One meme that circulates on the internet is “heart of the cancer is ANC.” (Anc is middle three letters of the word cancer)

“One of the things about South Africa is that we have a very poor government, a very corrupt government,” says Barend La Grange, chief executive of the Privilege foundation, an NGO which encourages mixed race groups to take ownership of their towns when the “government is not doing what it is supposed to do” regarding maintaining infrastructure. His foundation encourages townspeople to clean, repair, paint and plant to make their towns more attractive to investment and tourism, says La Grange. Basic stuff, but you need to start somewhere “The community must take over that task until we get a government that does the job it Is supposed to do. A lot of towns in South Africa are not looking good.”

One historian, Anthea Jeffrey, tells me South Africa’s problem is that the ANC are still basically communist. (They got support from the USSR during the Cold War.) The USSR may be long gone, but the old freedom fighters still have enormous influence. That means radical redistribution as well as policies that stifle personal initiative, income growth and business investment. Indeed, the EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters), a breakaway faction of the ANC, which may get a 10-15% balance-of-power share of the vote in 2024, calls for radical confiscation of whites’ still considerable assets, Zimbabwe style. It scares the hell out of the white professionals who remain. And it would almost certainly truly ruin South Africa economically.

Faldi Samaai is a civil engineer in Cape Town who employs mostly black engineers, half of them female, and is optimistic. The competence is the same, just give it time. Some of those whom he employs come from poor homes and are on scholarships. “They catch up, you know, I have no problems with their level of skill.” Some students take the first year of the university engineering course over two years, to help them catch up, so they graduate a year later. “But so what? In Germany people graduate on average at 28.”

While power engineer Chris Yelland thinks that South Africa’s injurious load shedding can be prevented by just a small addition of renewables feeding back into the grid, which legislation now provides for, President Ramaphosa having declared a national emergency over the power cuts. A massive roll out of PV solar panels to homes, even among the poor, is the way forward: the Chinese may be able to build a nuclear power station in six years, but as Kusile and Medupi show, these large-scale projects seem to be a bit too difficult for South Africa get right. So “individually implemented” solar could be a solution. Yelland says, “Bulk generation of power provides less jobs per unit of energy than distributed generation in the form of wind and solar. There are fewer jobs in the operating phase with bulk generation, plus the fact you have to rebuild renewable energy much more frequently. And if you look at all the rooftops, look at all the houses, shopping centres and parking lots and farms. You need people to design and install and maintain and replace and there’s a whole ecosystem that develops around rooftop solar PV. If you look at Vietnam that process of delivering 9000 megawatts solar PV battery storage for the commercial domestic sector was shown to be a big job creator.”

What my interviews show, there is a lot of initiative and inventiveness and effort to circumvent, or make irrelevant, what seems to be a hopelessly muddled efforts of a dysfunctional central government. Whether it will deliver prosperity to the many, and this prosperity creates a unified south Africa, or whether this self sufficient will create a series of pod communities, where the cleverest will collaborate on an ad hoc small scale level, with local firefighting, power generation and sewage works with large swathes of poverty swirling around them, remains to be seen. On the other hand, I was told that race relations were much better than ever, and there was a huge will in all communities to make a unified south Africa, ruled by a genuinely competent central government. South Africa may be more blackout nation than rainbow nation, but there is hope yet.

Pelle Taylor and Patrick Remington

Two Raven Films, Political and social documentaries

No comments.

By submitting a comment you grant Free West Media a perpetual license to reproduce your words and name/web site in attribution. Inappropriate and irrelevant comments will be removed at an admin’s discretion. Your email is used for verification purposes only, it will never be shared.