While we have learned a great deal from these communities, we have been unable to fulfill a common request: providing them their individual genetic ancestry results. In our attempts to overcome the logistical challenges of providing this information, we’ve grappled with the common question of how to ensure an equitable balance of benefits between researchers and the community they study. What we’ve found is that there is no easy answer.

The history of the Khoe-San

Community member requests to see their genetic results came as no surprise. Many South African groups were stripped of their identities and collapsed into one overarching racial category known as “Coloured” during the early 1900s. Early European colonizers initially used this term to refer to indigenous Khoekhoe and San groups long before it was codified by the apartheid government in 1948. It persists today as an ethnic category, broadly encompassing Khoe-San groups, various East African, Indian and Southeast Asian populations brought by the slave trade, and people of mixed ancestry.

We and other research groups have shown that some Coloured communities are largely descendants of the Khoe and San peoples. Other ancestries present in Coloured communities are from Bantu-speaking populations that migrated into the region from western Africa around 1,500 years ago and from Europe a little under 400 years ago. Asian ancestry is also present as a result of the aforementioned slave trade.

The Khoe and San are considered the most genetically diverse human populations currently known, meaning they have a large amount of genetic differences within and between each community. Though they are distinct groups, they share genetic similarities with each other. As a result, geneticists collectively refer to them as Khoe-San, using a hyphen to acknowledge their cultural distinction.

Today, few people identify as Khoe or San in South Africa. Rather, many people call themselves Coloured, though they are deeply aware of the term’s racist legacy.

Logistical challenges and potential risks

In our 12 years of fieldwork, we have returned to South Africa on a nearly annual basis to update community-level genetic results. At each visit, most of our participants ask about their personal genetic ancestry results.

But there are several hurdles we face in trying to fulfill their requests. For one, we need to be able to translate scientifically complex data into an accessible and digestible form, a skill that researchers are not always equipped with. Additionally, we must work within restrictions set by the local government, which is mediated by the Health Research Ethics Committee at our collaborators’ academic institution, as well as restrictions set by the South African San Council.

There are also potential risks to the participant. Group-level results provide a protective blanket from potential legal or social issues that can arise from individual ancestry results. For example, a participant may learn that their biological father is not who they believed they were, which could sow conflict in the family and unease for the participant. More generally, the participant faces the social risk of being included or excluded from different communities depending on the outcome of the results.

We discussed these potential problems with past participants and found that most community members care little about the risks. Our participants have consistently viewed the option to receive their personal ancestry results as a benefit of taking part in research. They simply want to know who their forefathers were.

Helicopter research and exploitation

To fulfill these requests, we’ve partnered with 23andMe Inc., a U.S.-based company that provides at-home genetic testing. One of us previously worked for 23andMe on its ancestry team and continues to maintain a relationship with scientists at the company. When 23andMe launched a program in 2018 to improve genetic data on underrepresented communities in biomedical and genetic research, we were excited to see an emphasis on local partnerships and community grants. We submitted a successful application, and 23andMe has provided us with funding to conduct this research.

As academic researchers, we don’t always have the right expertise on how to best communicate personal results. Nor do we often have the funds to successfully execute this task. Research grants do not typically provide support for community development, and graduate and postdoctoral researchers lack protected time to do this on top of their other responsibilities. 23andMe, on the other hand, already has the resources and the experience to accessibly communicate personal genomic results to lay people, because that’s its commercial product. Thus, collaborations with for-profit organizations is not uncommon. Along with 23andMe, academic researchers have also worked with genetic testing companies 54gene and Variant Bio.

With approval from the research ethics committee of the local university we work with, 23andMe will fund the expenses of our fieldwork and a community grant, in addition to processing our DNA samples in exchange for data access. They plan to use the data to improve African ancestry results for their customers and for their own research projects.

The company made over US$50 million in 2021, and its plans to use the genetic data it has accumulated from its customers to develop pharmaceuticals has not been without controversy in the U.S. The samples collected in our partnership with 23andMe, however, would not be used to develop new drugs. While our research focuses primarily on broadening scientific knowledge, and 23andMe does make an effort to follow an ethical framework for collaborations like these, our developing partnership has heightened our concerns about exploitation and what’s known as helicopter research.

Scientists conduct helicopter research when they collect data from developing countries and marginalized communities with little to no involvement from local researchers and community members. Helicopter research also occurs when researchers take data out of the country they collected it from without either providing benefit to or sharing the results with the community.

Informed consent is not enough to prevent research from being exploitative

San communities are no strangers to helicopter research. For example, hoodia is a cactus San communities use to suppress appetite during long hunts or famine. Pharmaceutical companies researched and patented this cultural knowledge in 1995 to develop and sell an anti-obesity pill, initially all without San recognition or involvement. If the San were acknowledged at all, they were referred to as a population that no longer existed. After several legal disputes, the San were promised benefits from any production that came out of the project. Though they received some compensation, it was a fraction of the value they funneled toward the research and nowhere near what was promised.

This has been a recurring issue for the Khoe and San communities, most recently involving the rooibos tea industry. Companies conducted over a century of commercial rooibos farming benefiting from Khoe and San cultural knowledge before finally agreeing to pay 1.5 percent of what farmers make for unprocessed rooibos to the communities. Because of this, gaining approval from the local university’s ethics committee for our project has been difficult, and understandably so.

To build a more active and transparent relationship with the local community, we are working closely with 23andMe to develop an advisory board of members from local communities. We have held town halls and conducted interviews with locals to ask if they’d still be interested in being a part of this research project if a company became involved. The majority expressed little concern about 23andMe’s involvement and potentially profiting from their genetic information. But history has shown that for study participants around the globe, informed consent has its limitations. It is still difficult to communicate and gauge whether participants, or the millions of Americans who have paid 23andMe for genetic testing, fully understand the full extent of the risks involved with giving away their genetic data, both to 23andMe and to us academic researchers.

The company has offered to provide small community grants to help meet local needs, and has also expanded our ability to “capacity-build” – that is, to make sure that the knowledge and skills we gain are shared with local institutions. But the question remains whether there is an equitable balance of benefits. Other companies have already promised long-term benefits by sharing equity and profit with participating communities. Are individual ancestry results and community grants a sufficient and fair exchange against the profits the company will gain from this collaboration?

Where does this leave us?

Academic researchers are faced with navigating the many trade-offs that come with industry collaborations. While 23andMe’s participation provides a means to return individual results to the community, it also raises questions about sufficiently equitable benefits. Our research team, local collaborators and 23andMe are all concerned about how to best address the risk of helicopter research, coercion and any unknown risks that may arise from disclosing personal ancestry results.

In an ideal world, researchers would be able to return benefits to the community without involving nonacademic external parties. Integrating practices like returning results to communities within research grant requirements is one way to ensure that participants are also benefiting from research. Nonprofit small grants dedicated to returning results and community benefit are another. Until then, researchers will continue to make do with the limited resources they have.

This article was updated to more accurately reflect how 23andMe will use the collected data.

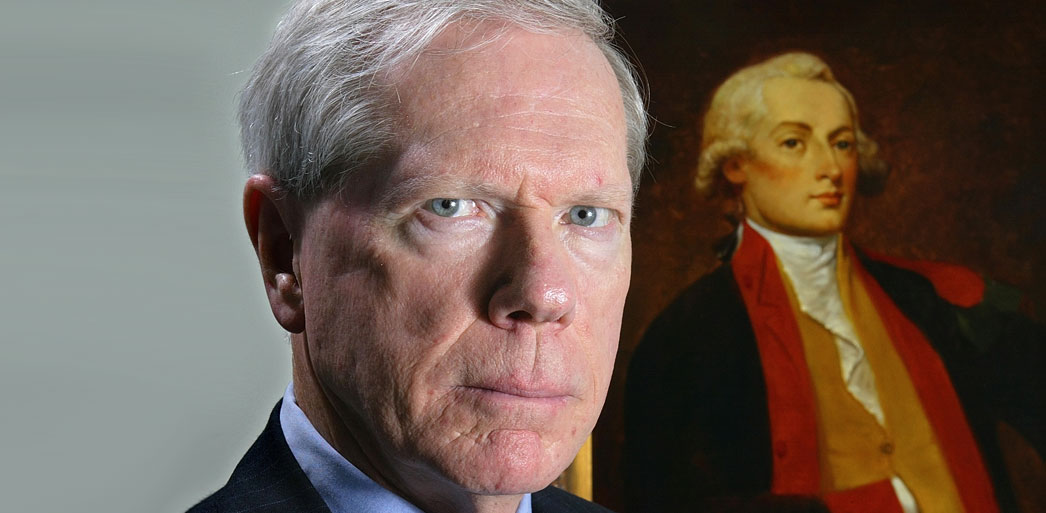

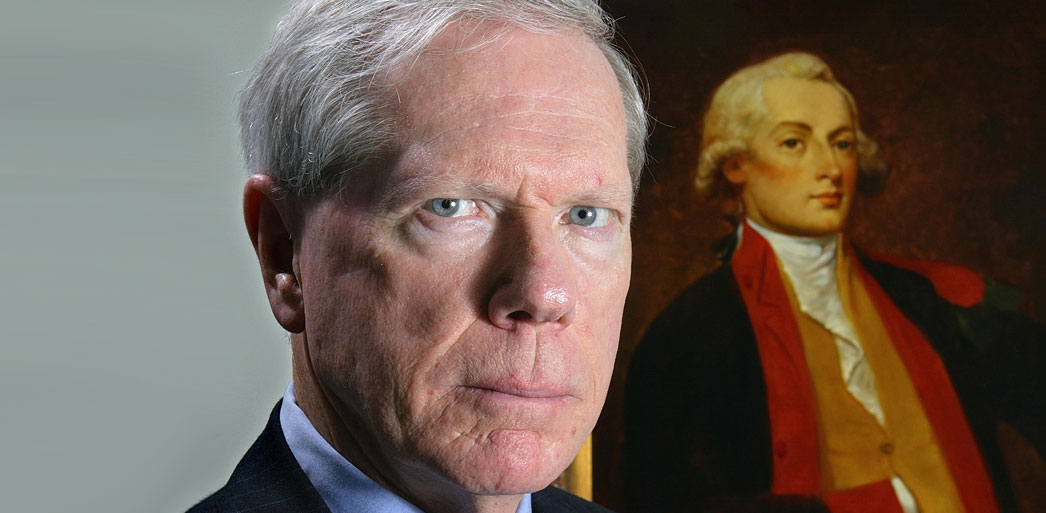

Dana Al-Hindi

PhD Candidate in Anthropology, University of California, Davis

Brenna Henn

Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Davis

Disclosure statement

Dana Al-Hindi intends to use Dr. Henn’s awarded funds from 23andMe Inc. to complete fieldwork and return of results to sampled communities.

Brenna Henn is a former employee of 23andMe, Inc. and retains shares in the organization. She has received funding from 23andMe to complete research described in this article.

University of California, Davis provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

The Conversation is funded by the National Research Foundation, eight universities, including the Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Rhodes University, Stellenbosch University and the Universities of Cape Town, Johannesburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal, Pretoria, and South Africa. It is hosted by the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Western Cape, the African Population and Health Research Centre and the Nigerian Academy of Science. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a Strategic Partner.